I spend a lot of time fixing people’s squats. A lot. I’m really good at it. I often find that my best success in fixing a squat comes when I have them do it wrong. It’s a great paradox and one that many people have a hard time accepting but it works.

I spend a lot of time fixing people’s squats. A lot. I’m really good at it. I often find that my best success in fixing a squat comes when I have them do it wrong. It’s a great paradox and one that many people have a hard time accepting but it works.

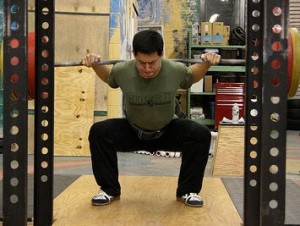

Many people fall backwards when they squat and their knees cave in and their weight shifts into their toes and their heels lift. Classic errors. When working with them I ask them what they are focusing on when they squat and the answer is always “Keeping my chest up.” I ask “Why?” They respond, I was told “I have to be upright when I squat.” It is that motivation to have their squat be more upright that causes their squat to look like shit. If you insist on trying to remain upright when you squat at the expense of all the other points of performance then you will forever have a shitty squat. If you are reading this and you can squat upright and keep your heels down and knees out and go thr ough a full range of motion and lift heavy weights, then continue to do so. That’s great. However, many many people cannot and, for the foreseeable future, should not bother with trying to maintain an upright torso.

ough a full range of motion and lift heavy weights, then continue to do so. That’s great. However, many many people cannot and, for the foreseeable future, should not bother with trying to maintain an upright torso.

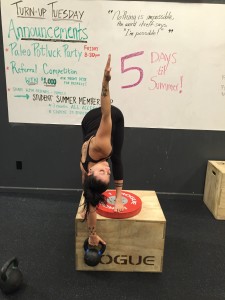

Please remember that I am not saying they should round their backs. A neutral spine should be maintained under load always, but the angle of the torso can shift to nearly horizontal while maintaining a neutral spine under load. Do not confuse “good” with “optimal.” An optimal torso angle is closer to vertical but a good squat with a non optimal torso angle is better than an upright squat on your toes.

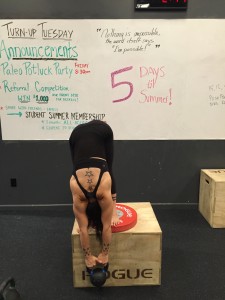

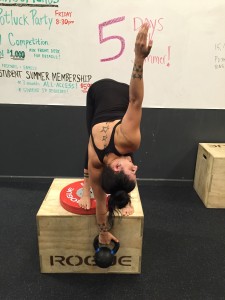

We often refer to uprightness in a squat as maturity and horizontal as immaturity. Think about why that is. A more mature and experienced lifter that has more years under her belt can evolve to a more mature position, but a beginner lifter will often have to train in less optimal positions before they can even access more demanding positions.

Here is why the immature squat works better for many lifters:

- They are better balanced. An athlete that is out of balance is inherently unstable and cannot access muscular control when the nervous system is preoccupied with not falling down.

- An immature squat allows the hips to sit back further and puts tension in to the posterior chain. Once the glutes and hamstrings are on tension they can fire better to drive the knees out and pull the knees back allowing more weight to settle into the midfoot and heel.

- An immature squat properly loaded can help strengthen the back muscles which allows the squat to be a great assistance exercise in developing the deadlift, clean and snatch which require the spine to loaded in a similar position.

- Greater flexion at the hip reduces the amount of flexion at the knee and ankle to achieve proper depth thus it is easier for athletes to squat to depth with their feet flat on the ground.

- It reduces a lot of knee pain symptoms associated with squatting upright. Primarily due to greater recruitment of the glutes and hamstrings as well as the reduction on knee flexion.

It’s okay if you don’t believe me, but find the worst squatter in your gym and see if it works on them. Don’t judge a squat by how it looks, judge it by it’s functionality. Can the athlete maintain a balanced position? Can they go through a full range of motion? Can they have their knees track their toes? Can they maintain a neutral spine? If these criteria are met, then don’t worry about how it looks. Let your athletes get strong with good mechanics. Once they have a better base of strength and have more experience, then go back in and see if you can improve their positions.

What about catching cleans and snatches? Maybe make your athletes get good at power cleans and power snatches before rushing to get them down into the bottom and receiving load in a bad position. Do not be in a rush. You can’t cram for strength. Crawl. Walk. Run.